Shreveport, Louisiana & Home-Grown Architecture

In the twentieth century, homegrown architects dominated Louisiana’s architecture. In the first decades, the firm of Favrot and Livaudais designed an extraordinary range of buildings in southern Louisiana, as did Emile Weil. Weiss, Dreyfous and Seiferth became the architects of choice for Governor Huey Long in the 1930s. Long’s ambitious reform and modernization programs led to major commissions for the design firm. Most notably, Weiss, Dreyfous and Seiferth designed a new state capitol in Baton Rouge, Charity Hospital in New Orleans, and university buildings throughout the state. Their buildings blended modern forms with the stylized, decorative elements of art deco.

But, it was in Shreveport that architects first broke with traditional historical styles, perhaps because the city had a less powerful architectural tradition than New Orleans. In the 1920s and 1930s, Samuel and William Wiener created buildings whose only precedent was the pure geometric forms of international modernism. Their work kept pace with new, post-World War II design ideals, and they produced innovative houses in Shreveport. World War II also generated new attitudes and goals in southern Louisiana, and several firms became nationally known, most notably Curtis and Davis. Vowing to design solely in a modern mode, the firm’s commissions in Louisiana included houses, schools, the extraordinary expressionistic Rivergate (since demolished), Angola State Penitentiary, and the Superdome. Inventive in their interpretation of modern forms, their buildings were as structurally innovative as any in the nation. Baton Rouge-based John Desmond also added some unique buildings to the state’s architecture.

Today the Wieners are remembered primarily for their trinity of International Style residences built between 1934 and 1937, all of which are currently ensconced on the National Register of Historic Places. The three white stucco masterpieces — the Wile House [1934], the Flesh House [1936] and the Samuel Wiener House [1937] — are all located in Shreveport’s South Highlands neighborhood and have either been maintained or restored to their original glory.

The Influence of Climate & Natural Resource

Climate and the availability of materials profoundly influenced the state’s architecture. Until air-conditioning became widespread in the mid-twentieth century, the semitropical climate was a prime determinant of architectural form. Buildings were raised off the ground both to counter flooding and encourage air circulation. Doors and windows were aligned for cross-ventilation, and deep overhangs shaded walls. Ample galleries provided outdoor living spaces, where residents might catch a cooling breeze, while high ceilings and roofs were designed to draw up the heat. These features are intrinsic to Creole cottages, shotgun houses, and, in northern Louisiana, dogtrot houses. Although not unique to the state, these house types are so ubiquitous that they have become identified with Louisiana.

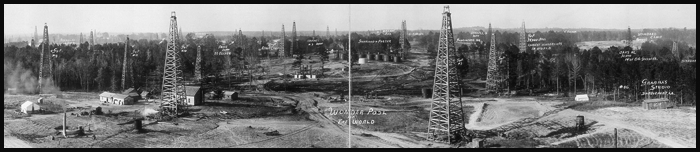

Louisiana’s cypress and pine forests provided building materials. Since the state lacked building stone, brickyards were quickly established, probably in the 1720s. For important buildings, the brick walls were often stuccoed and scored to resemble stone. When stone was shipped into the state, it was primarily used for major civic buildings. Because it was rare, stone gave these buildings a symbolic weight and presence, as well as physical strength. The monumental granite-walled Custom House, U.S, Customs House in New Orleans is the most obvious example. Southern Louisiana’s soft soils did not deter architects and engineers from constructing heavy stone buildings or, beginning in the late nineteenth century, skyscrapers. Instead, they devised ways to carry and stabilize such buildings, supporting them on piles sunk hundreds of feet into the soupy mix.

Geography and climate also shaped Louisiana’s economy. From early in the eighteenth century, plantations were established along the Mississippi River. Land was laid out on the French long-lot system, with the narrow end of the property bordering the river. This ensured that each property owner had access to the water. Sugar became the crop of choice in southern Louisiana, while cotton proved popular in the northern part of the state. Often huge agricultural enterprises, plantations consisted of a complex of buildings. The planter’s house took center stage, while slave housing, barns, sugar mills or cotton gins, and other necessary buildings were at a short distance. Some of the more magnificent plantation houses survive, many adorned with columns and other classical embellishments. Few of the ancillary dwellings, however, remain. Planters transported their products by river to the port in New Orleans, where sugar and cotton traders built handsome office buildings. They also transformed the suburb immediately upriver from the French Quarter into a vital commercial and business district. In the city’s growing suburbs, some traders commissioned enormous houses in the latest architectural styles.